The Ceramic and Glass Department of Bearnes Hampton & Littlewood, run by Nic Saintey and Andrew Thomas handles the full range of pottery, porcelain and glassware. Many hitherto unrecognised and important pieces have been brought to the market place through the department's enthusiasm and expertise. In excess of 3000 lots are offered every year.

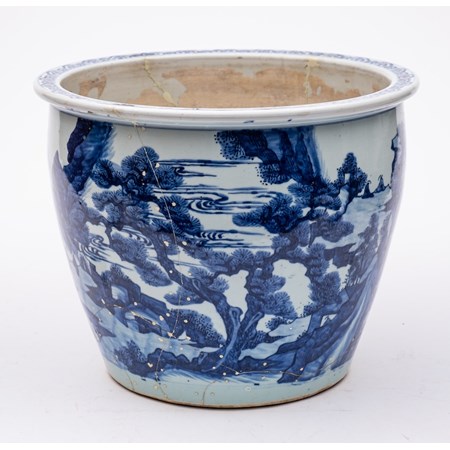

As ceramics become increasingly popular, so the fields of collecting broaden far beyond the traditionally strong market for 18th century English work. Our auctions include examples from most of the better-known English and Continental factories and an ever increasing amount of Oriental pottery and porcelain. The current trend for studio pottery often from living contemporary potters is also catered for. Many owners are also discovering that pieces bought in the mid-20th century have become sought after. Our reference library and extensive internet database can help to establish not only the value but also the full history of the piece.

The department also handles all aspects of glassware, from the best of French to early English and the decorative work of the 19th and 20th centuries.