Nadine Lundhal (b 1956). Still life, £2,000 (FS38/384).

My most memorable and enjoyable moment at an art exhibition was with Rothko at Tate Modern about 15 years ago. I had been introduced to Rothko at Summer School on an Open University art history course. If memory serves, OU Summer School was an opportunity for a middle-aged man to kick-back for a bit. Five days of timetabled tutorials, quite intensive study and socialising was a refreshing change - not to mention, educational.

The OU is a fantastic organisation. My experiences of tuition and support were outstanding and to the astonishment of most of the people I know, I became a BA, which was rather unexpected having not really grasped the importance of a qualification or two while I was actually at school. This is not to say degrees are the be-all, and I take my hat off to any young person getting out there and just getting on with it, degree or not.

So, having heard about Mark Rothko, a 20th century American artist who did Abstract Expressionism, and having seen some of his paintings in books, our tutor encouraged us to visit the Rothko Room at Tate Modern.

Here were the Seagram Murals, or at least some of the murals that were intended in the late 1950s for the Four Seasons Restaurant in the Seagram building in New York.

Mark Rothko was born in Latvia in 1903 and, to escape persecution, moved with his family to America in 1913. After the death of his father and an unsettled childhood, he found employment in Portland and became active upholding rights for workers and women.

Portland was a hotbed for radicals and anarchists, where labour unions were well organised and Rothko found a direction for his painting to take.

Back in New York in the 1930s, Rothko discovered the abstract-nature paintings of Milton Avery where form, space and fields of colour were the inspiration for him to believe he could exist as an artist.

Influences flow into Rothko's development as a painter including the psychoanalytical theories of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung. Rothko became aware of a spiritual emptiness in society with man trapped by the effects and influences of the modern world and he harnessed a desire to relieve this by reconnecting man with the potential and importance of dreams, myth and the unconscious.

In the 1940s, Rothko was influenced by Clyfford Still and abstract fields of colour are first referenced where blurred blocks of colour devoid of form and figure become a place where myth and subversion possess their own life force. In the late 1940s, Rothko, who through periods of his adult life is effected by depression, moves 'out' to Long Island and becomes reclusive and more selective of company. His reputation as a painter grows but simultaneously there is realisation that his work is being collected for nothing more than decoration and contemporary fashion and the purpose of his work was becoming lost.

For Rothko, paintings must possess their own form, potential and energy and must be encountered as such. The surface of paintings should 'push out in all directions, or rush inward in all directions' and Rothko emphatically states that 'between these two poles you can find everything I want to say'.

Then, in the 1950s Rothko, is commissioned to produce murals for the prestigious Four Seasons Restaurant in the Seagram Building in New York: The Seagram Murals. Rothko realises the opportunity and the potential to 'bring his monumental drama right into the belly of the beast'.

Work begins on dozens of large canvasses until 1959 when Rothko travels to Rome, Florence and Venice and revisits murals and frescoes by the Old Masters, including Michelangelo. Here he realises that painting can capture the viewer in a room. This revelation means the Seagram Mural project is doomed because Rothko would have to give-up his paintings to transient, pretentious and inappropriate dining rooms. He returns his cash advance and refuses to continue the project. This is how some of the amazing canvases now hang in the Rothko Room at Tate Modern.

So, it's not every picture or artist that change the course of art, culture and social history, but in Rothko I think there is an argument that some do. There is little doubt that either alongside or post-Rothko other painters draw inspiration and influence from the direction he took painting, either wittingly or unwittingly.

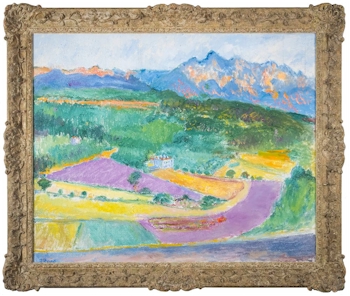

If the Nadine Lundhal Still Life grounds painting in the straight-forward representation of things, and the Gore Lavender Fields, Webb Hopfield and Drawbridge Night Landscape still are fields and landscapes, but possibly not any that actually exist, then where does that leave explaining Heron's January 1973 composition, or what do we make of a Modular Study by Alan Munroe? Answers on a postcard...

There are six major painting sales each year at Bearnes Hampton & Littlewood, including two sales dedicated to 20th Century & Contemporary work. For advice or to consign a picture please contact Dan Goddard

-hopfield.jpg)

"Clifford Webb (1895-1972). Hopfield, £780 (CC02/004)X

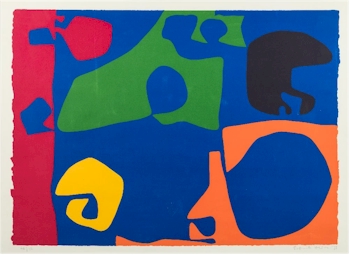

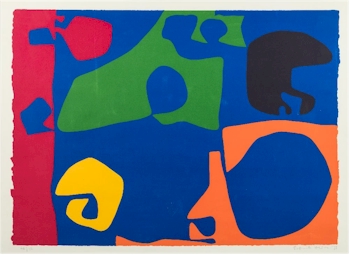

Alan Munroe (1926-2014), Modular Study - Mirror 21, £1,650(CC02/4).

"Patrick Heron(1920-1999). January 1973, £2,100 CC02/4).

"John Drawbridge (1930-2005). Night landscape, £2,000 CC02/352).

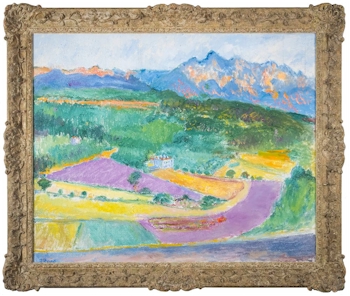

Frederick Gore (1913-2009). Lavender Fields, £6,500 (FS43/409).

- Bearnes Hampton & Littlewood

- Nadine Lundhal (b 1956)

- Clifford Webb (1895-1972)

- Patrick Heron(1920-1999)

- Alan Munroe (1926-2014)

- John Drawbridge (1930-2005)

- Frederick Gore (1913-2009

Mark Ruthko and 20th Century Art was written on Friday, 10th August 2019.

-hopfield.jpg)