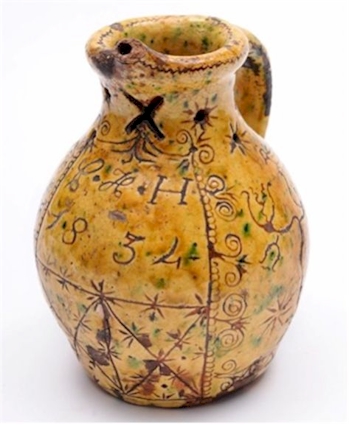

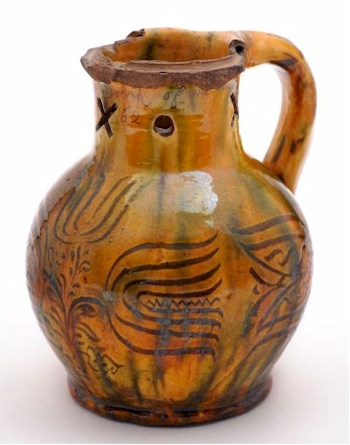

A Donyatt pottery puzzle jug with skinny hen decoration.

There must have been countless provincial potteries up and down the country selling practical wares to their neighbour, but with the passage of time almost all of them have literally disappeared from collective memory, save perhaps for the unearthed shards that appear whilst gardening. So why is it that we can recognise the sgraffito decorated Bideford and North Devon harvest jugs, a Verwood Owl or the classic mustard slip decoration on the chocolate brown Sussex pottery? Well apart from the appearance of names and dates within their decorative scheme, it is because either museums have maintained collections of their local pots or someone has written a book on the subject. So it is Richard Coleman Smith and Terry Pearson who deserve our thanks for writing the seminal volume on Donyatt pottery.

Donyatt is in the middle of central rural Somerset, part way between Chard and Ilminster and south of Taunton. Its name is derived from a pre-Doomsday chieftain called Dunna who cut a gatt or gap through the Neroche Forest to provide a track. Latterly this track became known as Crock Street, which rather hints at the pottery production that had occurred there since Norman times. Although the first 'recorded' pottery was in 1662 and the last closed in 1933, at its peak in the mid-19th century there were fourteen families potting concurrently.

One of the earlier potters worthy of mention was John Jewell who moved from Bideford to Donyatt in 1691, thus providing a link with an established industry in North Devon and one can perhaps as a result see more than a passing resemblance in the products of the two. Also worthy of a mention is George Norris who died on 24th November 1684. Whilst we have no clue as to his prowess as a potter, his will does provide a window on the life of a Donyatt potter. The sum allowed for 'all his potters weare and tyles' was £2 15s and 'all the ympliments and tools that belonge to his trade' 12s. Interestingly, these were dwarfed by 'all his hay’ £7 00s and livestock £24 00s, so whilst he was far from poor, the value placed on potters and pots seems pretty low.

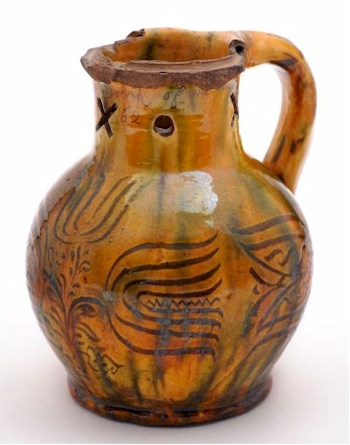

North Devon and Donyatt pottery, part of the same family.

This is backed up by records of the most prolific and continuous Donyatt potters, the Rodgers family. In 1756, there was mention of James Rodgers taking over the apprenticeship (from another potter) of a poor child from the parish of Ilminster, called James Rodgers, which it transpires was his own son. Subsequently, James junior is recorded as being in Honiton as he had run away before fulfilling his obligations.

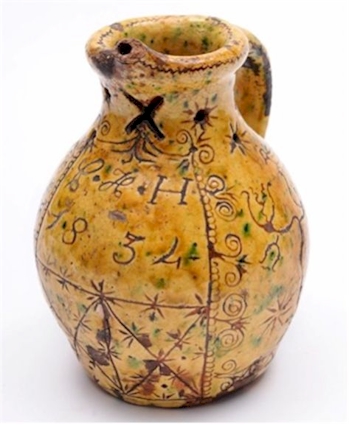

So what did the Donyatt potters make? Primarily, it was day to day practical wares, bricks, tiles, oven doors, cooking pots, together with bacon or fruit roasters that looked somewhat like a squat lectern, which one could place before the hearth. However, these are rarely seen outside of museums. From the 18th century onwards, it is crocks, bowls, vases, the odd fuddling cup, money boxes and lots of jugs, particularly puzzle jugs. When fired, the body of Donyatt wares has a red/orange colour and is covered in a custard coloured slip and clear glaze that often contains green flecks. The decoration is primarily sgraffito but some leaf stencilling occurs and the most common motifs are simple tulip-like blooms and rather skinny 'U' shaped birds or hens and plenty of text often relating to drinking especially on jugs.

Classic Donyatt custard slip with green flecked clear glaze.

Foliate stencilled decoration on a Donyatt vase.

A Donyatt jug with tulip decoration.

The classic red orange Donyatt body.

Being in the middle of nowhere, miles from the sea and not well connected by roads one can understand why Donyatt in the main didn't sell far afield. Also, when one compares it to the contemporary competition that did travel more widely, namely saltglazed stoneware, Whieldon and domestic delft pottery, it does look rather unsophisticated and parochial. Also, there was competition from other West Country potters such as Bideford and Bridgwater who, unlike the fragmented Donyatt potters, were able to fulfil bulk orders. You could say that it was doomed from the start.

The contemporary competition delft, saltglazed and Wheildon wares.

In the mid 1970s, a distribution map of archaeological sites indicated that significant numbers of wasters appeared as far as 60 miles away along the road towards London and in other directions as far as Plymouth and the North Somerset coast and across into Wales and surprisingly in five different sites in Virginia and Maryland. Taking this into account, you have to wonder why only twenty to thirty pieces seem to come up for auction each year. It begs the question: 'Where has it all gone?' Being unmarked, we can assume that some pieces do go unrecognised; that said, it would be great to see more as the demand for good Donyatt pieces remains healthy both here and in the United States.

- Bearnes Hampton & Littlewood

- Pottery

- Donyatt

Donyatt: A Pottery in the Middle of Nowhere was written on Friday, 26th July 2019.