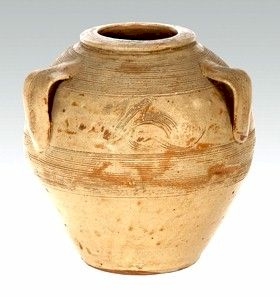

A Bernard Leach stoneware vase, circa 1947.

It could well be argued that Studio Pottery was the unexpected offspring of the Arts and Crafts Movement of the late 19th century. With hindsight, extolling the virtues of traditional craftsmanship would, sooner or later, elevate the practical provincial potter to that of artist. Also being constrained to locally available raw materials, nuances and customs could be seen not as a restriction, but the doorway to aesthetic beauty in a post-industrial society.

William Staite Murray and Bernard Leach, both born in the 1880s, might be considered inaugural members of the movement, though the former has largely fallen from wider recognition. Murray, along with Reginald Wells and Charles Vyse, were amongst the earliest students to attend the first ceramics only teaching course at the Camberwell School of Art in the early years of the 20th century – a move that signalled pottery ought to be considered on a par with painting or sculpture. Initially, much of the influence for these early studio potters came from the Orient, hardly surprising bearing in mind the proximity of the collections within the Victoria and Albert Museum. Murray as a new exponent of ceramic art felt that aesthetics would always trump functionality, something that seems passé nowadays, but to an Edwardian mind-set a beautiful vase that was impractical for flowers was quite radical.

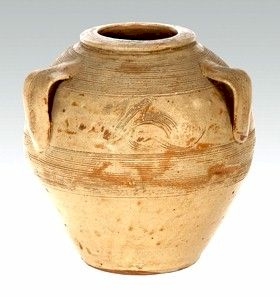

A Shoji Hamada 'Mongama' flower vase.

A Janet Leach stoneware vase, circa 1960.

Bernard Leach on the other hand felt that functionality was everything, being born in Hong Kong and living in Japan until the First World War, the influence of the East was all encompassing. In 1920, with the help of Shoji Hamada, he built a kiln at St Ives and attempted to meld western salt glazing and slip decorating with eastern techniques and philosophy. Widely acknowledged as the father of the movement, both in the founding sense and that he produced a dynasty of potters, students, apprentices and acolytes, many of whom are still potting today, it is little wonder that the 'Leach' way of doing things has been so resilient.

A Lucie Rie porcelain vase, circa 1975.

Studio pottery was not all 'brown and oriental', notable exceptions came in the form of Lucie Rie and Hans Coper. Rie already an established potter, fled Vienna in 1937, to seek out Bernard Leach. Whilst their respective philosophies were at odds, Leach did assist Rie to start designing and making glass and ceramic buttons, plus a later introduction to Heals and a stint teaching at the Camberwell School of Art.

A Hans Coper cycladic arrow head vase, circa 1978.

Although Bernard Leach considered her work to be outside of his established tradition, Rie's alternative path saw her produce a myriad of new thinly potted and dynamic shapes that 'flared like flowers under the sun'. In part, this new found belief came from her association with another wartime immigrant Hans Coper who literally turned up at the doorstep and asked for a job. An artist with designs on being a sculptor, he had no experience of potting but was a quick learner and was 'set to' on repeat work making buttons and cups and saucers for coffee shops.

By 1959 Hans had left for Cambridge to join the Digswell Project, a collaboration of mixed artists and craftsmen who believed that the prototype of every object should be designed by an artist, and was responsible for producing acoustic cladding and even a wash basin! However, he is most renowned for his bold abstract vases ironically were on ancient cycladic forms including the spade and arrowhead.

Outside the aforementioned exceptions, the century was driven by the Leach aesthetic, but at the dawning of the new century, there were plenty of new potters with refreshingly novel approaches that have becoming desirable; certainly in terms of what collectors are prepared to pay. Obviously a largely brown raw material is likely to remain a constraint but in the main, Oriental philosophy has been usurped by other concerns; particularly the influence of landscape which, can be seen in the work of some of these 'new kids on the block'.

Ewan Henderson open form, circa 1985.

Ewan Henderson, a student of both Rie and Coper favoured hand built sculptural pieces that were primarily abstract and asymmetric in form. A different kind of brown that he referred to as 'fluxed earth'. Particularly drawn by the natural world, he was fascinated by the alchemy of change, the transmogrification of earth into something else. The surface of his work having a volcanic appearance as a nod towards both the firing process and the geology that produces clay.

Peter Hayes 'immersed' pottery vase, circa 1983.

An altogether slower transition can be seen in the output of Peter Hayes whose stated aim is 'not to compete with nature; but for work to evolve within the environment'. This is reflected in his creation of sculptural pieces intended for outside and his acceptance that once in situ, the environment will continue to have a creative hand. He accelerates this process by submerging biscuit fired pieces in water for months on end, giving the element the opportunity to add to or leach from the clay and more overtly assist their evolution.

John Ward stoneware vase, circa 1983.

Another proponent of the hand built vessel is John Ward: much of his inspiration comes from the Welsh landscape he inhabits. Often using a matt palette of green, blue and ochres, he echoes the earth, sand, rocks and the very shoreline and by scraping or burnishing the surfaces of his pieces with pebbles they often, by association, take on a smooth weathered appeal and by subtly banding his colours, he mimics the action of water on rippled sand and the striations of coastal rock.

There is no doubt that without Bernard Leach there would not have been a Studio Pottery movement, or at least not one as strong as it had been for much of the 20th century. However, although it might seem sacrilegious to say so his exclusive aims, ideals and Oriental aesthetic have held sway for too long. Lucie Rie and Hans Coper as both potters and teachers helped to instigate change and as a result in the last few decades, there has been a vibrant interest in Studio pottery and the prices collectors are prepared to pay for it. One can only assume that this is because there are a now a multitude of competing ideas and approaches amongst ceramicists and that can only be a good thing.

- Bearnes Hampton & Littlewood

- Studio Pottery

- Hans Coper

- Shoji Hamada

- Peter Hayes

- Ewan Henderson

- Bernard Leach

- William Staite Murray

- Lucie Rie

- John Ward

Fifty Shades of Brown was written on Tuesday, 20th November 2018.