Three Thousand Years of Chinese Funerary Statues from Shang to Tang

A Tang Dynasty funerary statue of Lokopala, defender of tombs.

Long before Christians gave it consideration, the Chinese held a belief in the afterlife. Born out of a hierarchical society that believed in the deference of a child to a parent, this filial duty extended through the family and wider society beyond death. This ancestor worship was maintained partly through familial devotion, but also through a fear that failure to do so could result in spiritual disapproval, bad luck or even retribution.

Chinese funerary statuary at it's most lifelike.

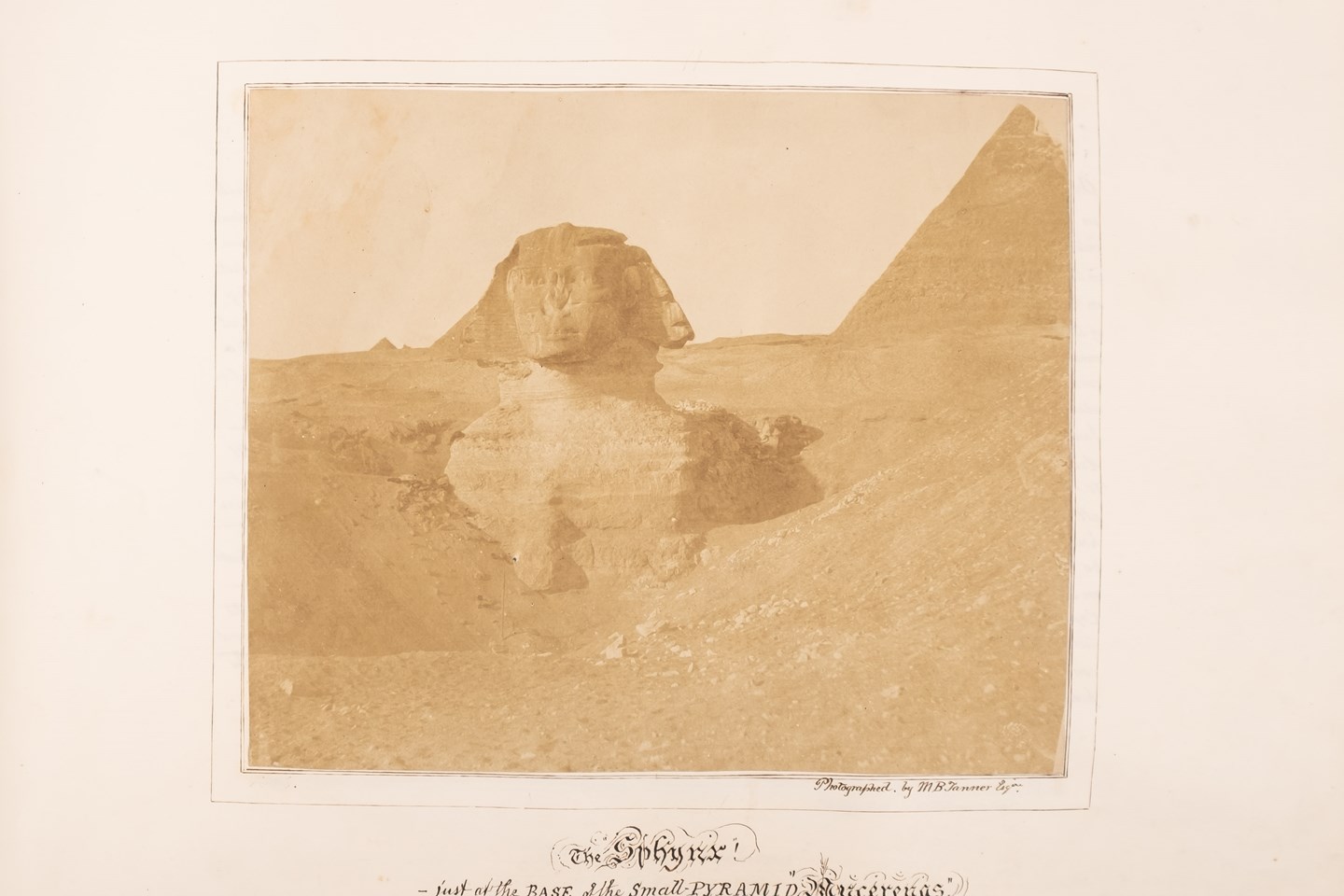

This duty permeated all Chinese society and included the Emperor, the good future of the state lay in his hands provided that he accorded his ancestors the proper offices. A great part of this devotion was to give the dead a good send off with everything they would require for the afterlife. During the Shang Dynasty (1523-1028 BC), royalty were buried in capacious graves with countless precious objects and a sacrificial human entourage. Senior staff would accompany the deceased, with their own coffins and objects, soldiers with their horses and weapons and finally junior staff and slaves were decapitated and interred with their master.

One can imagine that once the bar had been set high, this could have led to something of a funerary arms race with each subsequent generation fearing the displeasure of their immediate ancestor. Little wonder then that clay funerary sculpture started to be seen as a practical alternative to sacrifice, although on an imperial level this switch to clay didn't mean you could shirk your responsibility. The tomb of Emperor Qin who died in 210 BC is known worldwide as it contains the 'so called' terracotta army of some 8000 life size figures.

Humour in the afterlife: a Han Dynasty Balladeer.

Funerary stautuary at its best: a Tang equestrienne.

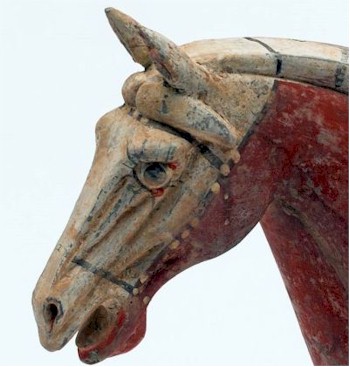

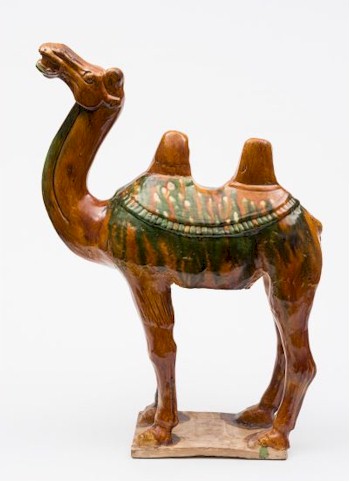

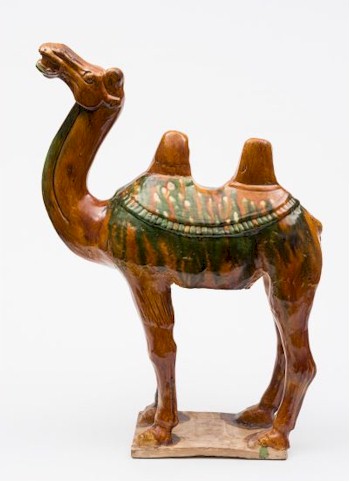

A sancai glazed Tang Dynasty camel.

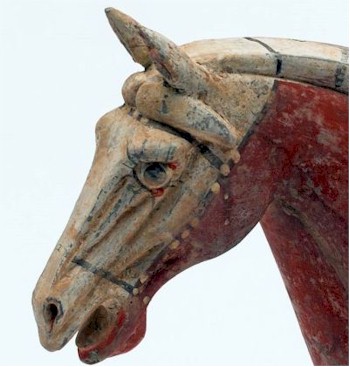

On a more modest level, the use of funerary sculpture became widespread during the Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD) and more prolific during the Tang Dynasty (618 AD–907 AD). Whilst none were now life size, the repertoire could include pottery officials, concubines, charioteers, soldiers, servants, grooms and musicians, often with hand painted details to add an air of individual character to them. There were animals such as horses and camels for transport, oxen and carts and even pigs, dwellings and sometimes fields of crops and tables laden with meat, fruit and other tasty morsels.

An entourage of Tang Dynasty tomb attendants, each holding a Zodiac animal.

Effigies of a rather ferocious individual known as Lokapala were also interred along with equally disturbing earth spirits and grave guardians whose job as the name suggests was to keep the ill intentioned at bay and the cache of spiritual life support objects for whom they were intended. The use of funerary statues and grave goods continued until the fall of the Ming Dynasty in the 17th century, when presumably the practise fell out of favour with the ancestors, who then allowed the rival Qing Dynasty to prevail.

Ming Dynasty votive furniture and food: a feast fit for an emperor.

These culturally fascinating, ancient and once high status objects are striking in their modelling. The bulging eyes and flaring nostrils of a horse can often give it a real sense of vitality, no mean feat for a piece of inanimate clay and, despite the serious intent behind some of the stiff looking courtiers and soldiers, there are also funerary figures bordering on caricatures that have a homely sense of fun and day-to-day humanity about them that a contemporary observer would recognise.

Whether there is an afterlife or not I feel sure that even in the vastly different environment of the 21st century they'd be good company.

- Bearnes Hampton & Littlewood

- Chinese Ceramics

- Funerary Statuary

- Shang Dynasty

- Han Dynasty

- Tang Dynasty

- Ming Dynasty

- Qing Dynasty

Grave Concerns About Death was written on Wednesday, 24th February 2016.